for info about price, etc please contact: cynthia.guest@gmail.com 646 573-3630

|

| 30. 19th Century Baby, German, Oil on Canvas 20" x 20" Offered $675 SOLD |

31. Wendy Schultz Wubbels, Scherenschnitte 2001, 9" x 9" Offered $85 SOLD

32. Maria Martinez: World-Renowned Potter of San Ildefonso Pueblo

Maria Martinez (1884 - 1980)

Of Tewa heritage of the San Ildefonso Pueblo in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, Maria Martinez became world-renowned for her black-on-black pottery.

Learning to make pots as a child from her aunt, Tia Nicolasa, and beginning with clay dishes she made for her playhouse, Maria was known as a potter among her peers. In 1908, Dr. Edgar Hewett, New Mexico archaeologist and director of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, had excavated some 17th century black pottery shards and, seeking to revive this type of pottery, Hewett was led to Maria. Through trial and error, Maria rediscovered the art of making black pottery. She found that smothering a cool fire with dried cow manure trapped the smoke, and that by using a special type of paint on top of a burnished surface, in combination with trapping the smoke and the low temperature of the fire resulted in turning a red-clay-pot black.

Maria, who made but never painted the pottery, collaborated with her husband Julian, who not only assisted in the gathering of the clay and the building the fire, and, most importantly, painting the motif on the pottery. Julian painted Maria's pottery until his death in 1943. During the early years of pottery making, Julian broke away from farming to became a janitor at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe. It was here that he and Maria studied the pottery in the display cases, observing form, motif and technique.

Maria was always deeply connected with her pueblo of San Ildefonso, with the traditional life of a tribal member, partaking in tribal ceremonies and religious activities. Although she was successful in Santa Fe selling her pottery, she preferred living in her ancestral home. Maria was very unselfish with her talent, and she gave pottery lessons to other women in her village as well as in to potters in neighboring pueblos, thereby providing a new source of income to many. After her husband's death, she worked with her sons, Popovi Da and Adam, and her daughter-in-law, Santana in continuing her work throughout her life.

Maria Martinez became so admired for her skill that she was specially invited to the White House four times, and she received honorary doctorates from the University of Colorado and New Mexico State University. She is considered one of the most influential Native Americans of the 20th century.

Of Tewa heritage of the San Ildefonso Pueblo in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, Maria Martinez became world-renowned for her black-on-black pottery.

Learning to make pots as a child from her aunt, Tia Nicolasa, and beginning with clay dishes she made for her playhouse, Maria was known as a potter among her peers. In 1908, Dr. Edgar Hewett, New Mexico archaeologist and director of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, had excavated some 17th century black pottery shards and, seeking to revive this type of pottery, Hewett was led to Maria. Through trial and error, Maria rediscovered the art of making black pottery. She found that smothering a cool fire with dried cow manure trapped the smoke, and that by using a special type of paint on top of a burnished surface, in combination with trapping the smoke and the low temperature of the fire resulted in turning a red-clay-pot black.

Maria, who made but never painted the pottery, collaborated with her husband Julian, who not only assisted in the gathering of the clay and the building the fire, and, most importantly, painting the motif on the pottery. Julian painted Maria's pottery until his death in 1943. During the early years of pottery making, Julian broke away from farming to became a janitor at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe. It was here that he and Maria studied the pottery in the display cases, observing form, motif and technique.

Maria was always deeply connected with her pueblo of San Ildefonso, with the traditional life of a tribal member, partaking in tribal ceremonies and religious activities. Although she was successful in Santa Fe selling her pottery, she preferred living in her ancestral home. Maria was very unselfish with her talent, and she gave pottery lessons to other women in her village as well as in to potters in neighboring pueblos, thereby providing a new source of income to many. After her husband's death, she worked with her sons, Popovi Da and Adam, and her daughter-in-law, Santana in continuing her work throughout her life.

Maria Martinez became so admired for her skill that she was specially invited to the White House four times, and she received honorary doctorates from the University of Colorado and New Mexico State University. She is considered one of the most influential Native Americans of the 20th century.

In the 1920's my mother spent the summers riding with her cousin on the old Native American trails in New Mexico. The pot below is from one of those trips - the San Ildefonso Pueblo was one of her stops. The Medicine Man painting that follows the pot was collected then as well.

|

Fine Quality Maria Martinez Pot circa 1920's - 30's Offered $3200

Offered $575 SOLD

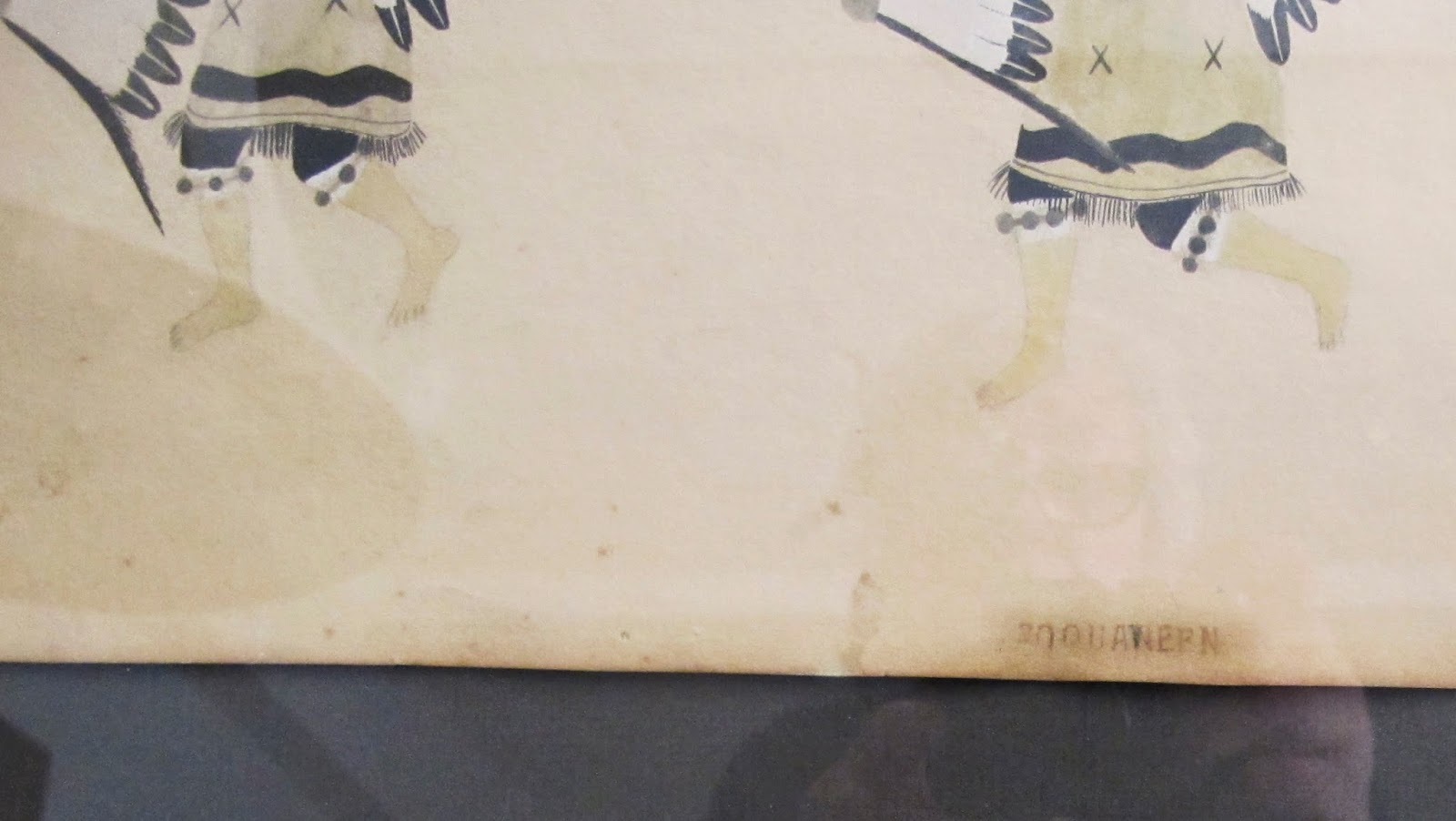

33. A nephew of the famous potter Maria Martinez, José Encarnacion Peña was one of the students of Dorothy Dunn at The Studio

of the Santa Fe Indian School in the early 1930s. He had, however,

started painting earlier, as early as the 1920s and continued until his

death in 1979. His complete name was José Encarnacion Peña and his

Native name was spelled Soqueen, Soqween, So Kwa A Weh, translated to Frost on the Mountain. Those who remember him in his later years recall that he was called Enky (pronounced “inky”).

Peña was painting at San Ildefonso at the

same time as Tonita Peña, Ricardo Martínez, Luís Gonzales, Abel

Sánchez, and Romando Vigil. He was not very productive in the early

years but became so about ten years before he passed away. He is

represented in the collections of the Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa

Fe; Museum of New Mexico; Denver Art Museum; and many others.

Soqueen’s earlier paintings from this

period had a primitive aspect, as one would expect of an artist without

formal training. His attention to detail was meticulous and his

renderings of figures were sensitive and delicate. His paintings reflect

a more realistic approach to painting what he saw and knew from pueblo

life, that a more artistic approach for decorative purposes.

|

34. Can't Read Signature, Anyone Know Who This Is By? - Poster Size Offered $975 SOLD |